Python Decorators Demystified

This articile was published earlier on Medium.

Decorators are one of the elegant features of the Python programming language. They are heavily used in modern libraries and frameworks.

The decorators are very good tools to encapsulate lot of implementation details and leaving out very simple interface. Let’s look at the following example:

@login_required

def edit_post(post_id):

...

The login_required is a decorator that makes sure that the user is logged in before they can edit a post. It’ll take care of redirecting to login page, setting the right query parameters to redirect back to same page after successful login etc. All that the developer of the function has to do is, put @login_required before the function.

While using decorators is very simple, writing decorators is something even experienced Python developers get confused lot of times. In this article I’m going to explain how Python decorators work in a few simple steps.

Functions are first-class objects

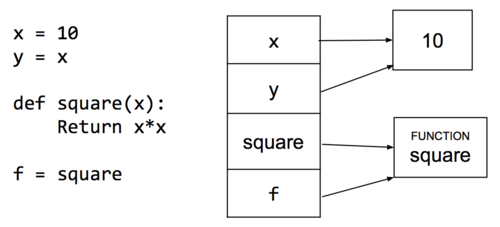

In Python, functions are first-class objects. That just means that functions are values just like numbers, strings and lists. Let’s look at the following example.

def square(x):

return x*x

print(square(4))

## 16

The output of the example is shown in comments at its bottom.

The above def statement creates a function square and assigns it to a variable with the same name. So we’ll be able to use that variable like just any other variable. For example, we’ll be able to assign it to another variable.

f = square

print(f(4))

## 16

The following picture explains the same thing clearly.

Functions can take other functions as arguments

Now that we know functions are nothing special, they can be passed as arguments to other functions. For example, the following function takes a function and two numbers as arguments.

def sumof(f, x, y):

return f(x) + f(y)

print(sumof(square, 3, 4))

print(sumof(len, “hello”, “python”))

## 25

## 11

And nothing stops us from returning a function from a function call.

def make_adder(x):

def add(y):

return x+y

return add

add3 = make_adder(3)

print(add3(4))

## 7

Since the function add is defined inside the make_adder function, it’ll have access to the variables of that function. So the code in the add function can access the variable x defined in the enclosed scope.

When make_adder is called with 3 as argument, it returns an add function with x set to 3. When we call make_adder again, it returns a different add function, with possibly different value of x.

Functions can take variable number of arguments

In Python, it is possible for a function to take variable number of arguments.

def strjoin(sep, *words):

return sep.join(words)

print(strjoin("-", "one", "two"))

print(strjoin("-", "one", "two", "three"))

## one-two

## one-two-theee

The above strjoin function receives its first argument in the variable sep and all other arguments packed as a tuple in the variable words.

It is also possible to do the reverse of that. If we have a list (or tuple) of arguments that we want to pass to a function, we can unpack them when making the function call.

def add(x, y):

return x+y

args = [3, 4]

print(add(*args))

## 7

Here is another example:

def info(*args):

print("[INFO]", *args)

def warn(*args):

print("[WARN]", *args)

info("connection established")

warn("hand shake failed. retrying...")

## [INFO] connection established

## [WARN] hand shake failed. retrying...

Decorator is just a syntactic sugar

The @decorator syntax is a shorthand for something really simple. For example:

@decorator

def func():

...

is equivalent to:

def func():

…

func = decorator(func)

The decorator takes a function as argument and returns a function back, possibly a new function.

Let’s write a simple decorator to understand it better.

def trace(f):

def g(x):

print(f.__name__, x)

return f(x)

return g

This trace function takes a function as argument and returns a new function that behaves like the original function, except it prints the function name and argument for every call.

@trace

def square(x):

return x*x

@trace

def double(x):

return x+x

print(square(4))

print(square(5))

print(double(4))

print(double(5))

## square 4

## 16

## square 5

## 25

## double 4

## 8

## double 5

## 25

There is one drawback of this decorator. This can work only with functions that take one argument. Usually, decorators are written to handle functions with any number of arguments. Lets improve our trace decorator to work with functions taking any number of arguments.

def trace(f):

def g(*args):

print(f.__name__, args)

return f(*args)

return g

And here is an example of using it:

@trace

def square(x):

return x*x

@trace

def sum_of_squares(x, y):

return square(x) + square(y)

print(sum_of_squares(3, 4))

## sum_of_squares (3, 4)

## square (3,)

## square (4,)

## 25

With a little more work we can make it print very nicely.

level = 0

def trace(f):

def g(*args):

global level

# pretty print indicating the level

prefix = "| " * level + "|--"

strargs = ", ".join(repr(a) for a in args)

print("{} {}({})".format(prefix, f.__name__, strargs))

# increment the level before calling the function

# and decrement it after the call

level += 1

result = f(*args)

level -= 1

return result

return g

With this trace decorator, the previous sum_of_squares example would produce:

|-- sum_of_squares (3, 4)

| |-- square (3,)

| |-- square (4,)

25

It would be fun to try it with a recursive function. Let’s try it with the famous fibonacci function.

@trace

def fib(n):

if n == 0 or n == 1:

return 1

else:

return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

print(fib(5))

See what it produces:

|-- fib(5)

| |-- fib(4)

| | |-- fib(3)

| | | |-- fib(2)

| | | | |-- fib(1)

| | | | |-- fib(0)

| | | |-- fib(1)

| | |-- fib(2)

| | | |-- fib(1)

| | | |-- fib(0)

| |-- fib(3)

| | |-- fib(2)

| | | |-- fib(1)

| | | |-- fib(0)

| | |-- fib(1)

8

Now, we have a beautiful decorator to trace function calls!

Hope this article made you understand how Python decorators work.

Thanks to Shreyas Satish reading draft of this and suggestions.

If you are excited about decorators and curious to learn more about them, check out my upcoming Python Decorators Demystified online workshop being held on Nov 21-22, 2020. It is going to be a hands-on workshop with lot of examples and practice problems covering some advanced use cases of decorators.